When magic happens in five milliseconds

Interview

"Photography is a great form of occupational therapy for me"

At eye level with his "models": nature photographer Dr. Igor Siwanowicz.

When did your passion for photography start?

Actually, I only started taking photos when digital technology became both affordable and was capable of delivering high quality images. I never had patience for film, or learning about techniques from books. Digital technology offers instant results and therefore an opportunity to make corrections on the go; the learning curve is very steep, and there is no cost associated with failures. Photography is a great form of occupational therapy for me because it grounds you in the moment when magic happens in five milliseconds.

What techniques do you use for taking your pictures?

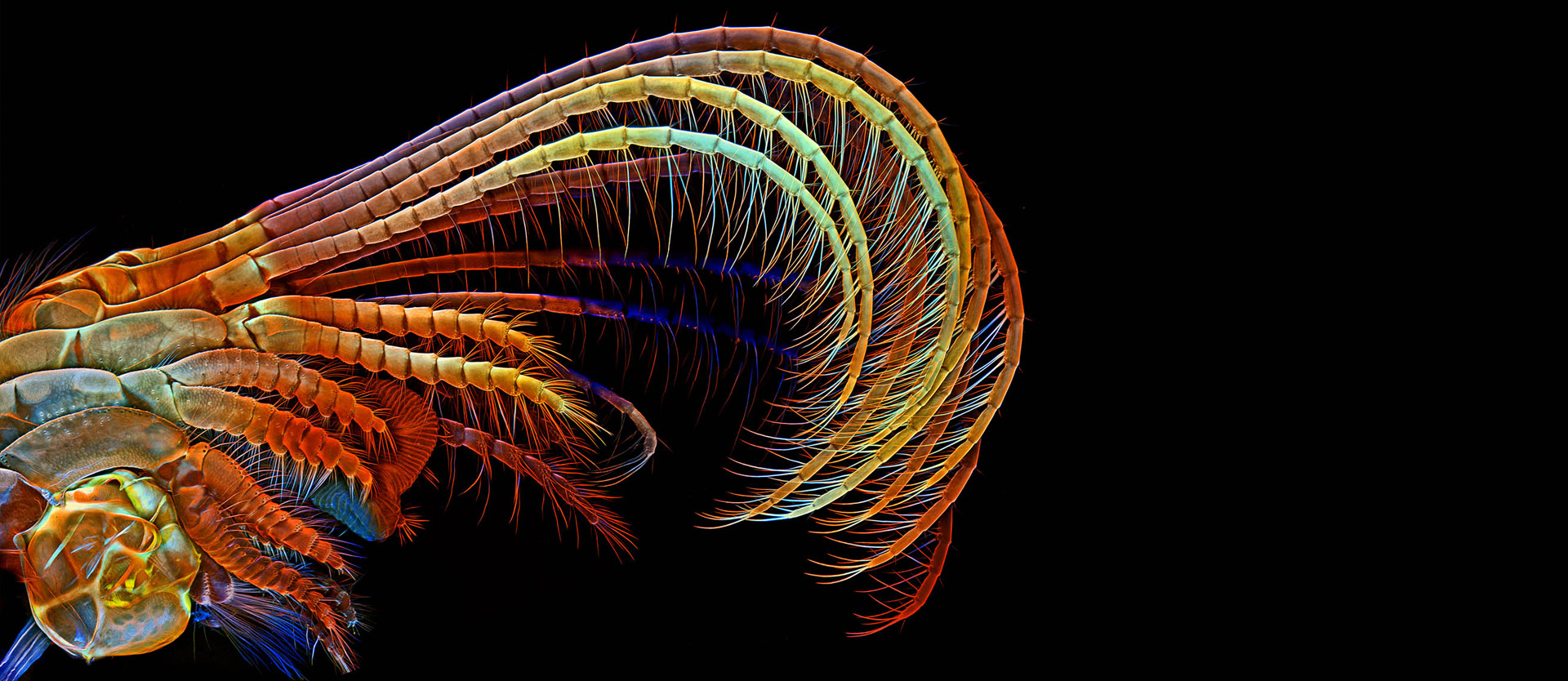

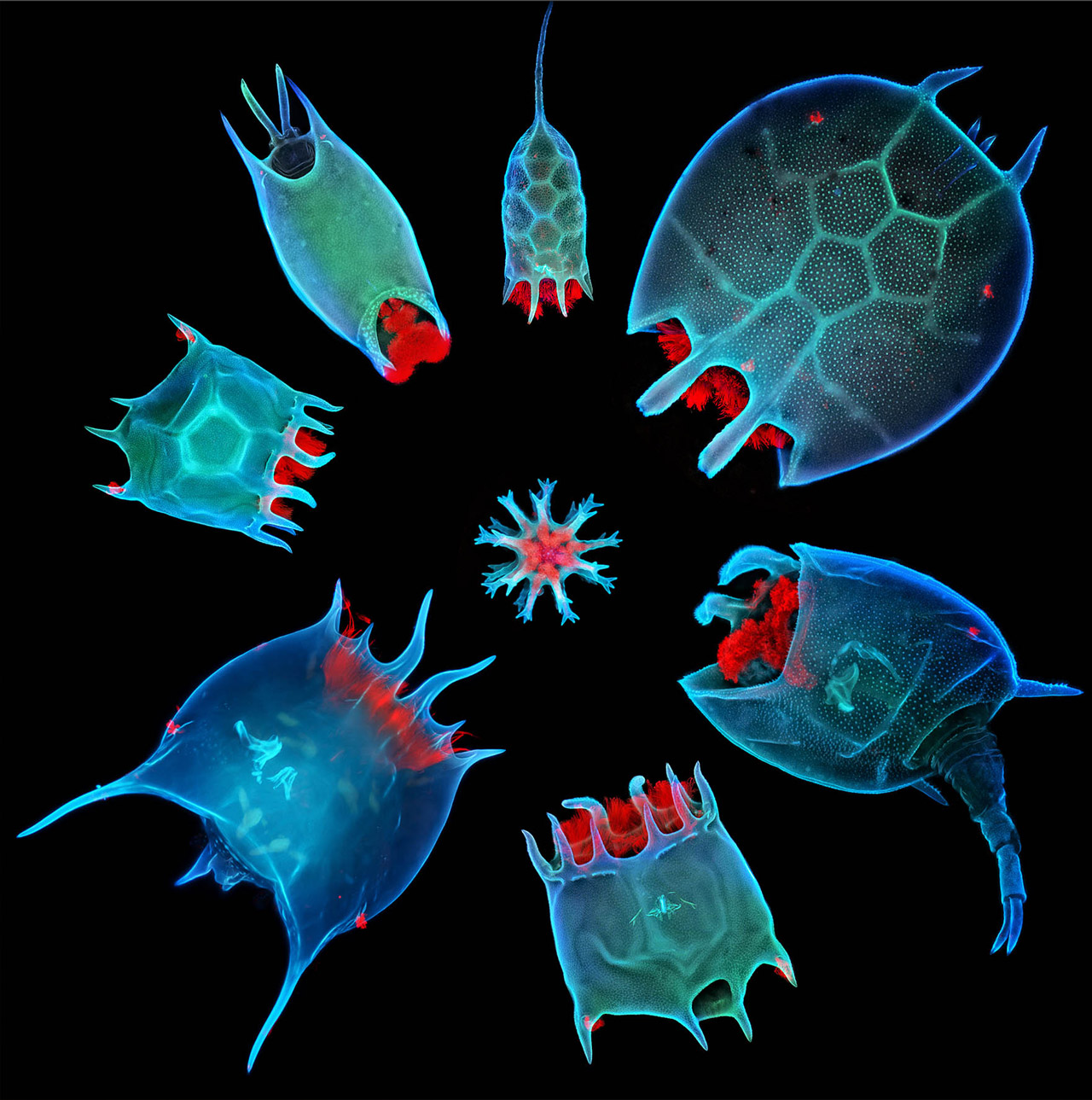

My photomicrographs are taken through a laser scanning confocal microscope, an imaging technique that uses lasers to scan three-dimensional samples. I first inject dyes into the neurons of interest. A laser then excites the dyes so that they emit light - it’s the same physical phenomenon that makes black light posters from the ’70s glow. The microscope that registers that light takes a series of images of the tiny specimen by scanning it point by point. Because the specimen is much thicker than the plane of focus, a series of images - called “stack” - is collected by moving the sample up or down. From those “optical slices” a three-dimensional image of the neurons within the sample can be reconstructed.

How much magnified do we see the insects?

II don’t use very high magnifications – most of the images in my collection are taken with a 10x objective, so the objects are magnified 100-fold. I also use 20x, 25x and 40x objectives giving magnification of 200, 250 and 400-fold. Some samples, due to their size, need be tiled – i.e. scanned multiple times as slightly overlapping stacks that are later merged, or stitched, together.

How do you edit your photos?

I consider image processing software such as Photoshop as much part of my workflow as the camera. I don’t manipulate or alter the subject matter, except some cases that are very obviously photoshopped, but I do tweak the global and local contrasts and the colour space until I’m satisfied with the result. In that sense, I’m definitely not a photography purist!

Ornaments of life are skillfully staged by Dr. Igor Siwanowicz.

Photographers play with light. Are there differences between the setting of light in macro- photography and conventional photography?

The lighting setup in macro photography is pretty much the same as in conventional photography. I’m using some variant of a three-point lighting, which in a classic studio setup consists of the key light, directed on the subject, a back light, also referred to as rim light, to get that brighter outline on one side of the subject, and a fill light, to soften the shadows and reduce harsh contrast. Also, a background light is often used to illuminate the backdrop behind the subject. Because macro photography is so much more compact, I can get away with using just two strobes to illuminate the scene: my back light often doubles as the background light, and if necessary I can also bounce it off a sheet of paper to mimic the fill light. I’m using an infrared flash transmitter to control the strobes mounted on individual light tripods. That allows me to move the light sources around and also to control the ratio of their output.

Diffusing the strobe light is essential, especially when shooting insects; their exoskeletons are often very glossy, and you don’t want to end up with over-exposed reflections. Softening can be accomplished by using relatively small softboxes. You attach them directly to the strobes. The whole setup – two flashes with their own tripods and diffusers plus a set of backdrops - fits easily inside a moderately sized backpack.

Recently I’m skewing towards using natural light; because its intensity is lower than that of the strobes, longer exposure times are needed so the subjects need to be rather stationary.