Fossils from boring times

For the first time, researchers at TU Berlin have studied the shape of microorganisms from the early days of evolution, 1.5 billion years ago. They provide information about the early development of life.

"It is fascinating that we are able to see the fossils of primordial microorganisms under the scanning electron microscope here for the first time," says a delighted Professor Dr. Gerhard Franz from the Institute for Applied Geosciences at TU Berlin.

"It is fascinating that we are able to see the fossils of primordial microorganisms under the scanning electron microscope here for the first time," says a delighted Professor Dr. Gerhard Franz from the Institute for Applied Geosciences at TU Berlin. "Actually, we wanted to examine beryl and topaz from the mine. But what we have now found is much more valuable than gemstones." The finds are the first fossilized microorganisms to date from the "boring billion," the first, seemingly boring billion of years before the so-called Cambrian explosion. This is because only about 600 million years ago, evolution invented skeletons made of calcium carbonate and phosphate. Invertebrates like mussels, corals or snails developed and then the vertebrates with backbones. This biomineralization made real fossils with preservable skeletons possible in the first place.

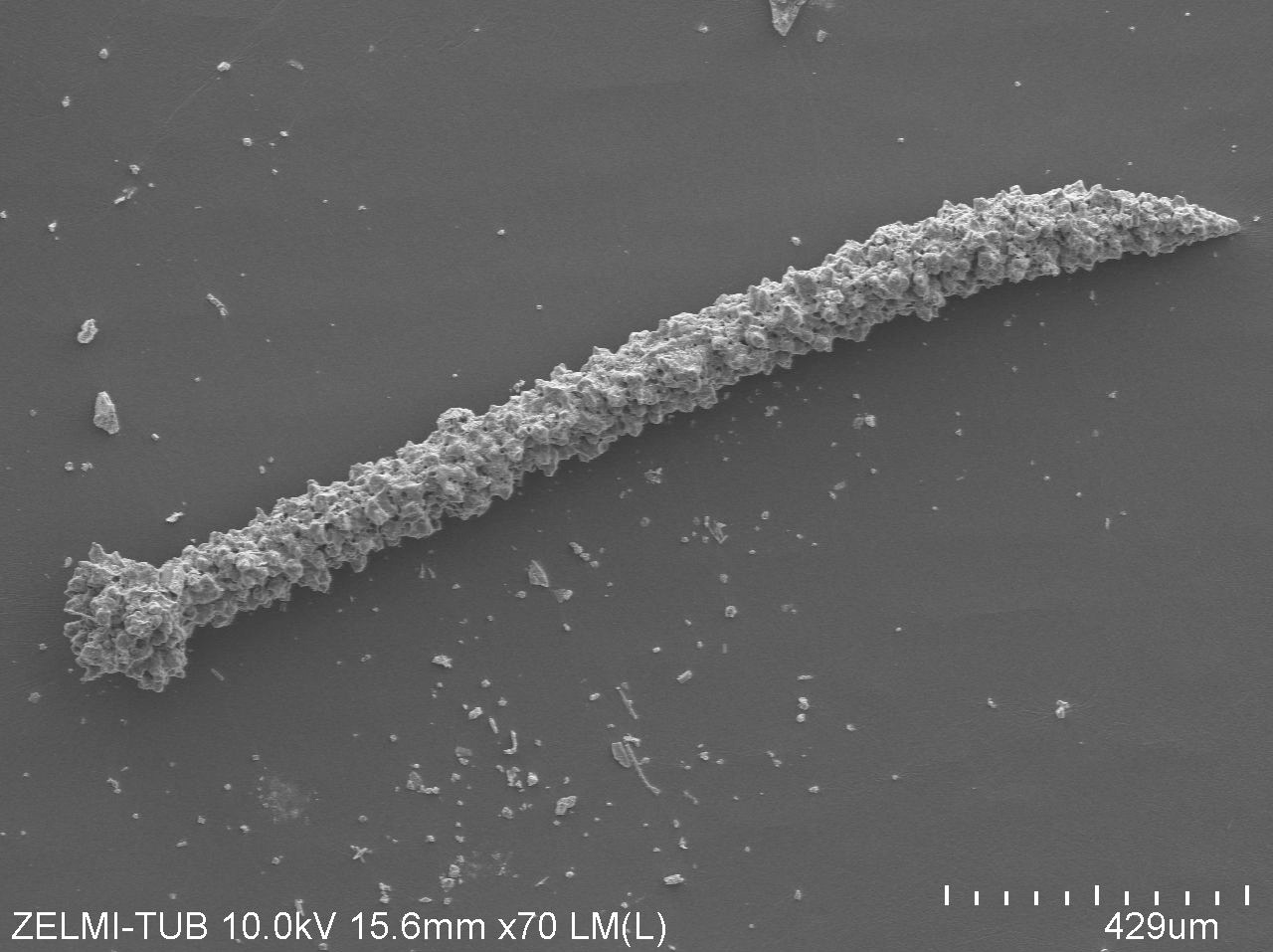

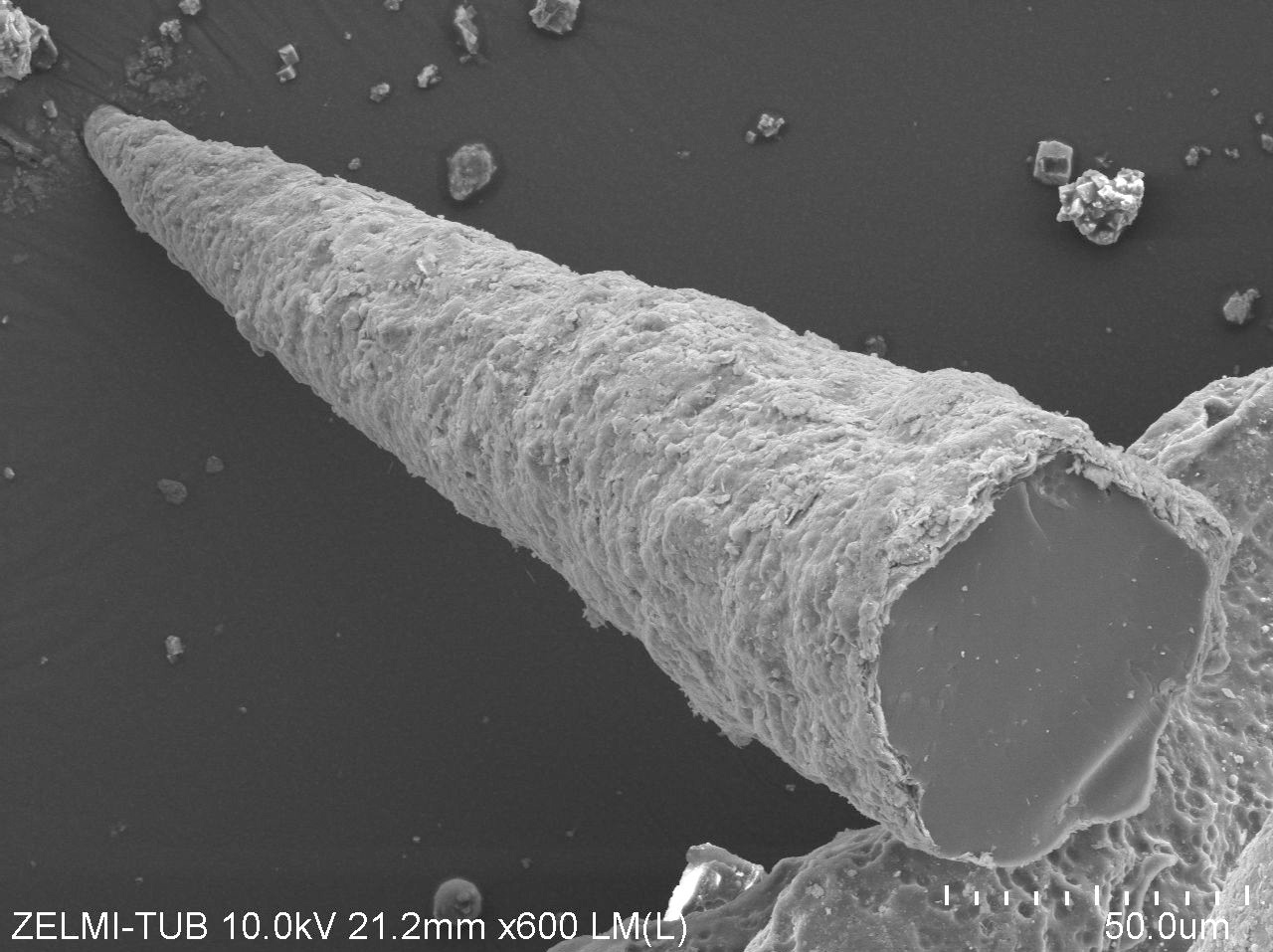

Because living things had no skeletons more than 600 million years ago, they could not actually preserve their form. That's why little is known about that time. "What we have found now is more valuable than precious stones," says Gerhard Franz. "Under the electron microscope, we see mostly fibrous structures. Either thin filaments that branch out, or thick ones that have protuberances and dents." The thickness varies from tens to 200 micrometers, and the length is up to several millimeters. It is therefore also possible to recognize the primordial microorganisms with the naked eye. Particularly exciting: The researchers also found a few previously unknown forms of microorganisms. They exhibited shell- or spherical-shaped structures or branched, tentacle-like branches.

"Using carbon isotopes, we were able to prove that they were living organisms," Gerhard Franz explains.

"Using carbon isotopes, we were able to prove that they were living organisms," Gerhard Franz explains further. The dating revealed an age of at least 1.5 billion years. In addition, the researchers used infrared spectroscopy to detect the substance chitosan in some filamentous objects, as well as the elements bismuth and tellurium. "That suggests a fungus-like organism," Franz says. But that's true of only some of the finds. "Of the other fossilized microorganisms, we suspect that they were single- or multicellular organisms with distinct cell structures." These probably lived with the fungi in an ecosystem.

The location of the fossilized primordial microorganisms on granite rock in a quartz mine suggests both their way of life and the reasons for their good state of preservation. "Even today, microorganisms exist up to three kilometers deep in the Earth's crust," Franz explains. They live there on substances such as phosphorus, nitrogen or carbon dioxide, some of which are dissolved in water and migrate downward from above through crevices. The microorganisms obtain the energy for their metabolism from chemical processes on minerals. In the granite caverns of the Volyn quartz mine, such colonies were apparently already present near the Earth's surface 1.5 billion years ago. And because granite contains a lot of fluorine, strongly corrosive hydrofluoric acid was formed with water and heat in the underground, which dissolved a lot of aluminum and silicon. Like a geyser, this solution shot into the caverns from time to time, covering the microorganisms with a micrometer-thin layer of aluminum silicate. "Of course, the microorganisms were dead afterwards, but they were also just perfectly preserved," says Gerhard Franz. "Further studies and perhaps new finds will tell us more about the primordial microorganisms, especially about the previously unknown forms on the continents, and not only in the sea," says Franz. "This could provide new insights into the early evolution of life on Earth, but perhaps also into the evolution of life under extreme conditions on other planets."

Original publications:

Gerhard Franz, Vladimir Khomenko, Peter Lyckberg, Vsevolod Chournousenko, Ulrich Struck, Ulrich Gernert, and Jörg Nissen

The Volyn biota (Ukraine) – indications of 1.5 Gyr old eukaryotes in 3D preservation, a spotlight on the “boring billion”

Biogeosciences, 20, 1901–1924, doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-1901-2023, 2023

Gerhard Franz, Peter Lyckberg, Vladimir Khomenko, Vsevolod Chournousenko, Hans-Martin Schulz, Nicolaj Mahlstedt, Richard Wirth, Johannes Glodny, Ulrich Gernert, and Jörg Nissen

Fossilization of Precambrian microfossils in the Volyn pegmatite, Ukraine

Biogeosciences, 19, 1795–1811, doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-1795-2022, 2022